by Heather Noble, RD

Maintaining fluid balance is extremely dynamic- constantly changing and fluctuating. Staying hydrated throughout the day and during exercise can be a real struggle for many athletes! These losses occur mostly through sweat during exercise, and if not adequately replenished, can lead to an increase in core temperature, impair normal bodily functions and negatively impact athletic performance. We can help prevent dehydration by making sure we are consuming fluids throughout the day, as well as before, during and after exercise.

Sweat and electrolyte (Calcium, Magnesium, Sodium) losses are very individual and vary greatly depending on the environment and conditions. The evaporation of sweat is the primary method for your body to cool off during exercise. The more trained the athlete, the greater amount of heat is produced during exercise, and the body adapts by becoming more efficient at cooling off by increasing its sweat rate. Therefore, trained athletes sweat sooner and more during exercise.

Our bodies need more fluid during hard training days or training blocks, in hot and humid conditions, and at the beginning of periods of heat acclimatization. Make sure you also stay well hydrated during recovery days, while travelling, training at altitude, and times of illness. Your body’s sense of thirst is often delayed until you are already partially dehydrated, making it very important to have a hydration plan designed specifically for your individual sweat and electrolyte losses.

During exercise, athletes typically lose between 0.5-1.2L/hour in cool conditions, and 1.0-2.0 L/hour in hot conditions. As little as a 1-3% change in body weight (BW) from fluid loss has been seen to negatively affect aerobic (Ex: marathons, triathlons) and cognitive performance. Greater fluid losses of 3-4% has been shown to further impair strength (Ex: weight lifting, CrossFit) and anaerobic (Ex: sprinting, high-intensity interval training) performance. A 1 kg of BW loss translates to 1 L of fluid lost through sweat.

Extreme dehydration (>5% BW) can cause serious medical conditions and must be avoided. It can place a significant strain on the cardiovascular system and compromise the body’s ability to regulate temperature. This will lead to an increased core temperature and increase the risk for developing heat disorders (heat stroke, heat exhaustion, etc.).

Signs of mild-moderate dehydration during exercise:

- Muscle fatigue

- Decline in coordination and cognition

- Muscle cramps

- Headaches

- Dry mouth

- Decreased energy

- Decreased sweat rate

Weight-class athletes who are purposefully dehydrating for rapid weight loss in order to weigh-in before a race should work with a Registered Dietitian or other sports professional and be closely monitored during this time. A rehydration plan should be created in order to minimize the impact of dehydration on performance.

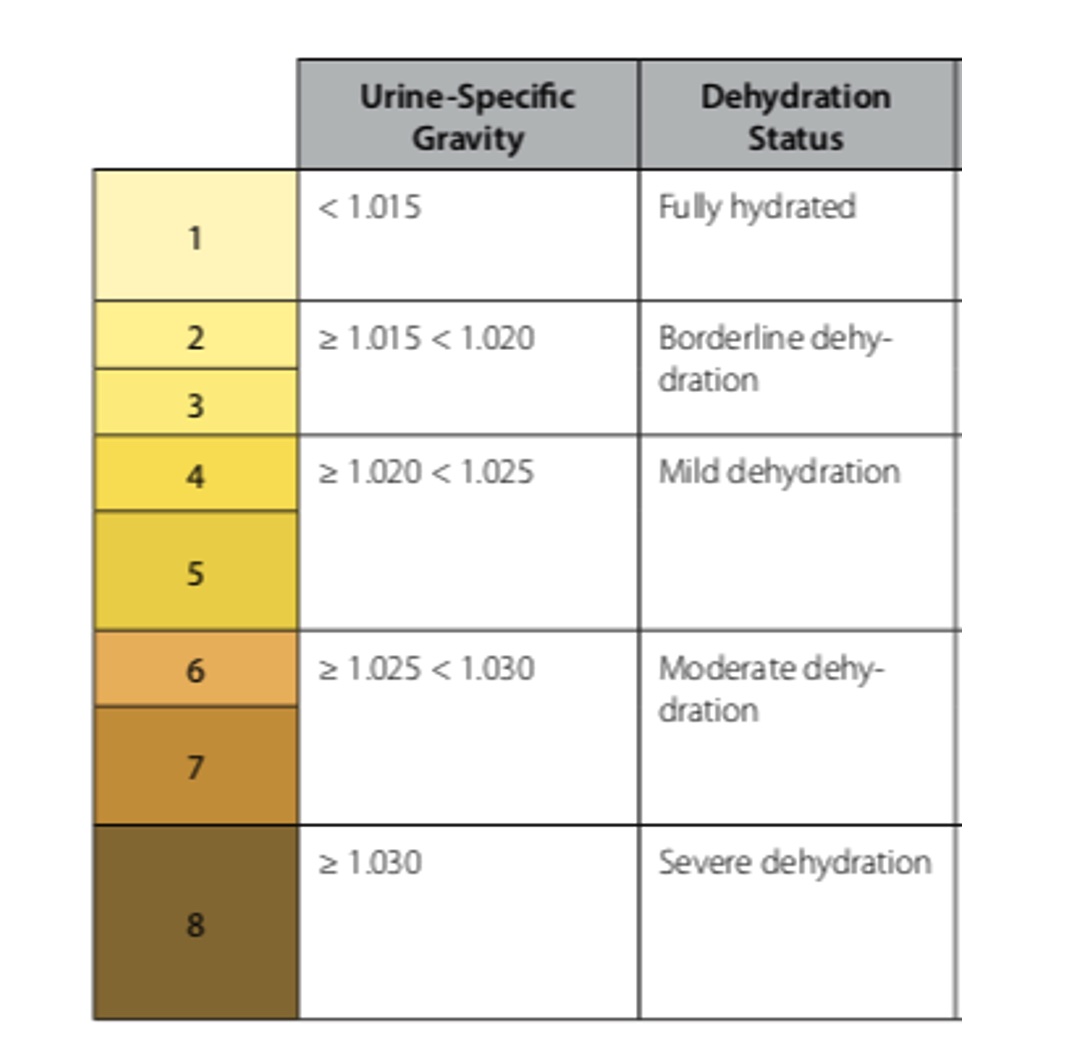

The Urine Chart below is a useful tool to help monitor hydration status. Urine Specific Gravity (USG) is a method of measuring urine concentration, however will slightly vary for each athlete depending on body weight and muscle mass. Aim for lemonade coloured urine at all times.

Tips on how to stay hydrated throughout the day:

- Drink approximately 500 ml water with meals to help with better fluid retention. Sodium is found in many foods which helps retain fluid.

- Always have a water bottle with you when you leave the house.

- Drink cold fluids during exercise and flavours that you enjoy.

- Keep a large jug of water on the table as a reminder to drink and fill up your water bottle as needed.

- Add some sliced fruit to your water to add some flavour.

What to drink before exercise:

- Most individuals lose 1 L (1 kg BW) of fluid overnight. You can determine this yourself by weighing yourself before bed and again in the morning (after going to the bathroom and before any fluid/food intake).

- Aim to drink approximately 500 ml 3 hours before exercise.

- Closer to race time aim to have 250 ml of water.

What to drink during exercise:

- For most training sessions, water is the best choice.

- Consuming simple carbohydrates (sports drinks, gels, high-carb foods, etc.) during exercise longer than 60 mins should be considered in order to maintain energy levels and exercise intensity. Choose drinks that have 14-15 g carbs in 250 ml and 100 mg of sodium.

- For prolonged activity (>60 mins), aim to consume 30-60g/hour carbohydrates, or up to 80g/hour as tolerated. Consuming carbohydrates during exercise actually teaches the body to adapt through “gut training”. Over time, the body is able to absorb and tolerate larger amounts of carbohydrates during exercise.

- Aim to consume 200-350 ml of water or sports drink every 15-25 mins during exercise.

- Avoid energy drinks around or during exercise.

- Cold fluids can help to cool the body in hot climates.

- Consider wearing a belt or carry a small water bottle when running. Plan your route to refill your water bottle for long exercise sessions.

What to drink after exercise:

- Athletes must rehydrate 150% of what was lost or 1.5L/kg of weight loss.

- Aim to consume easily digestible sources of both carbohydrates and protein post-exercise. Appetite is commonly suppressed after high intensity exercise, so drinking your calories can be a great way to get in fluid, protein and carbohydrate for optimal recovery. Ex: Chocolate milk or fruit smoothie with tested isolate whey protein powder.

- Take sips of water throughout the rest of the day to help rehydrate and 500 ml water with meals.

Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia (EAH)

More does not mean better! Athletes need to be cautious of drinking too much fluid (overhydration) during prolonged exercise as it can lead to EAH. Hyponatremia- “hypo” meaning low, and “natremia” is the Latin name for sodium. This is where the blood becomes excessively diluted from drinking too much water leading to dangerously low levels of sodium (below 135 mmol/L). This can occur during or up to 24 hours after prolonged exercise.

The development of EAH is likely the combination of excessive water intake beyond the capacity of your kidneys ability to excrete enough water. Although this condition is rare, it can lead to very serious consequences. To help prevent this, make sure to have a hydration plan and never drink too much where weight is gained during exercise.

Some final reminders:

- The water content found in food also counts towards total fluid intake (soups, smoothies, fruits, etc).

- Make sure you have a hydration plan for racing. Work with a Registered Dietitian or other sports professional. Practice this plan during training sessions and make any changes as needed.

- Adequate hydration is absolutely essential in maintaining optimal performance and recovery.